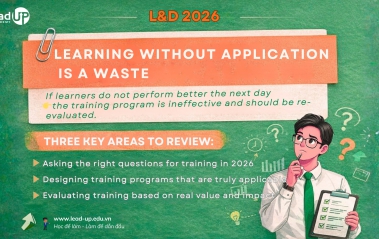

L&D 2026: Learning Without Application Is Wasteful

Across many organizations, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises in Vietnam, learning and development initiatives are implemented on a regular basis. Annual training plans are established, budgets are allocated, and participation rates are generally high. Classroom engagement is often positive, and post-training evaluations frequently reflect high levels of satisfaction.

L&D 2026: Training Should Begin with Operational “Bottlenecks”

In the context of 2026, Vietnamese enterprises are simultaneously facing several critical challenges: increasing pressure to optimize costs and improve productivity; workforce volatility, particularly within operational teams and middle management; and a widening gap between strategic intent and execution capability. Through its R&D activities and practical implementations across multiple industries—including banking, telecommunications, services, hospitality, real estate, and manufacturing—Lead-UP Academy presents in this article a clear and consistent message:

AI Does Not Replace L&D - AI Forces L&D to Be Rebuilt

In recent times, as Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been increasingly discussed in executive meetings, a recurring question has emerged: “Will AI make L&D redundant?” In some organizations, this question is taken even further: “Is it still necessary to invest in training when AI can already provide answers to almost everything?”

Coaching and Mentoring Gen Z in Vietnamese Enterprises

In modern human resource management, the 9 Box Grid (Performance – Potential) model is commonly used to classify employees. For Gen Z, this is an important tool that helps organizations identify who needs additional professional training, who requires coaching to improve performance, and who should be mentored to develop leadership potential. This context shows that coaching and mentoring are not merely management techniques but strategic approaches to building a sustainable succession pipeline.

Adaptive Learning Culture & Practical Training

When training fails to deliver results, it not only wastes resources but also creates negative sentiment, making it harder for the organization to implement future programs. Turning Every Course into “Learning to Act – Acting to Grow”

Developing Successor Teams

During a working session with a large manufacturing company in Southern Vietnam, I heard a troubling story: the plant director suddenly resigned to join a competitor. The problem was not about hiring a replacement, but about the fact that the company had no one ready to step in immediately. More than 300 workers were left waiting for direction, production plans stalled, and customers complained about delayed orders.

VI

VI EN

EN